A heuristic for direct measurement of donation after cardiac death donor potential

Thomas Mone2, J. Thomas Rosenthal MD1, Tom Seto3, Rosemary O'Meeghan4.

1Governing Board, OneLegacy, Azusa, CA, United States; 2Administration, OneLegacy, Azusa, CA, United States; 3Information Technology, OneLegacy, Azusa, CA, United States; 4Organ Operations, OneLegacy, Azusa, CA, United States

Purpose: Thousands of potential donors are referred for donation after cardiac death (DCD), yet a small percentage become donors. The factors that result in exclusion from donation have not been well described. The results have been regulations that use indirect measures of donor potential and confusion about organ procurement organization (OPO) performance. The purpose of this study was to spur dialogue about DCD rule out causes by categorizing, quantifing, and validating reasons that potential DCD donors did not progress to donation from a single large OPO that uses a comprehensive electronic donor record with robust clinical data.

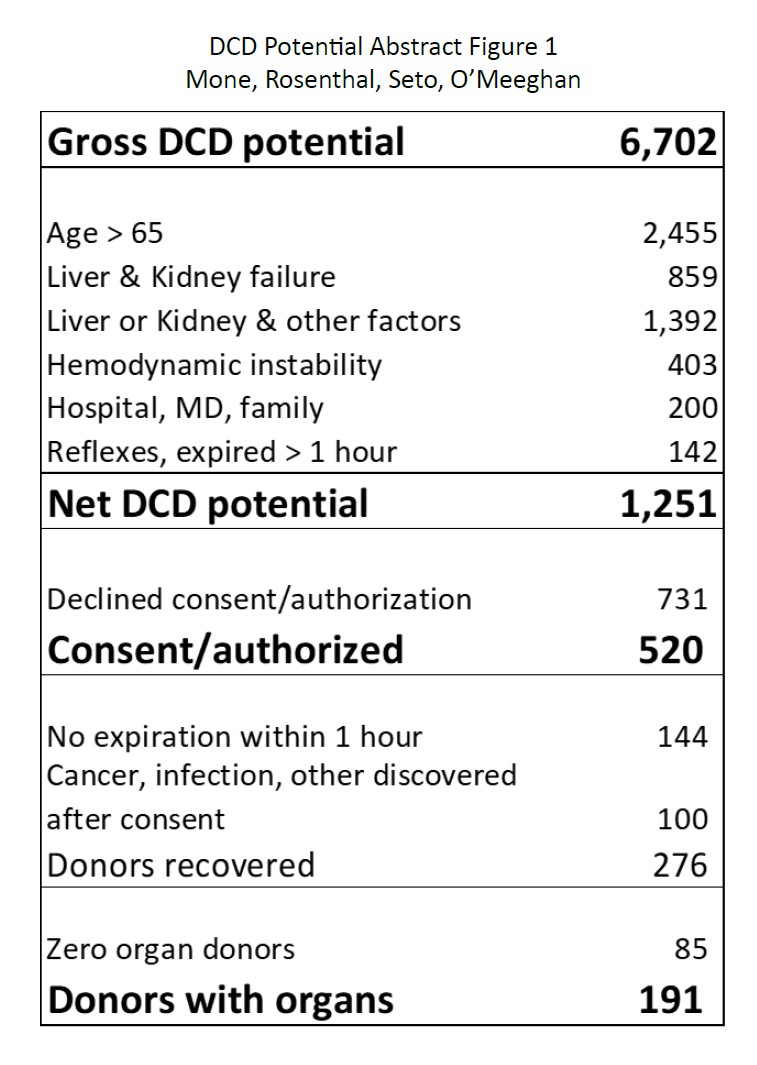

Methods: 18,685 potential donors were referred to OneLegacy in 2021 & 2022. 7,715 had cancers, infections, and age > 75; 1,116 suffered cardiac death without withdrawal of life support; 1,482 survived, and 1,670 progressed to brain death. For each of the remaining 6,702 potential DCD donors, donor records were reviewed and a reason for not reaching donation was assigned for each case. Almost every case had multiple reasons, but only the most significant cause is identified in the results. Organ dysfunction was diagnosed by laboratory and clinical findings, and hemodynamic instability was low blood pressure for extended periods, despite maximum pressors.

Results: The table shows how 6,702 potential DCD donors became 191 donors. The majority of rule-outs were due to organ dysfunction and age and were based on OPTN-defined standards and transplant centers’ acceptance practices. Criteria for donation rule-outs are codified in UNOS policy and assumed to be the same for DCD as brain death (BD). But because warm ischemia is always a factor in DCD cases, unlike BD, age cutoffs and organ discard criteria are in practice lower for DCD than BD.

Other differences with DCD: families, treating physicians, and hospitals have more autonomy from OPO involvement to withdraw life support prior to donation viability than in BD, resulting in cases where life support is withdrawn without OPO-family discussion about donation; further a significant number of DCD cases are not recovered because of failure to expire within an medically viable time after life-support withdrawal (usually 1 hour), including cases that are taken to the operating room and cases that are closed because reflexes remain present.

Conclusions: Measuring OPO performance has been fraught, because measurements of DCD potential have been indirect, such as including DCD as the percentage of BD donors. Direct measurement of donor potential would facilitate OPO performance improvement, enhance hospital and MD participation, improve public trust, and provide a more accurate and meaningful measure for comparative performance. For there to be a usable direct measure of donor potential DCD donor criteria must be codified, like BD, and incorporate factors unique to DCD. The categories and definitions identified in this analysis may be helpful in beginning that work.