Use of mechanical versus manual chest compressions in the recovery of uncontrolled DCD kidneys

Richard Hasz1, Sharon West1, Christine Radolovic1.

1Gift of Life Donor Program, Philadelphia, PA, United States

Introduction: Manual chest compression (MCC) devices used to maximize patient survival in emergency medicine and critical care settings for patients in cardiac arrest can also sustain the viability of organs for transplantation when patients are unable to regain spontaneous circulation. Given that only 20 of 14,905 deceased donors recovered in the United States in 2022 were recovered as uncontrolled DCDs, there is most certainly an opportunity to increase uncontrolled DCD donation through the development of protocols including use of mechanical chest compressions in the management of potential organ donors.

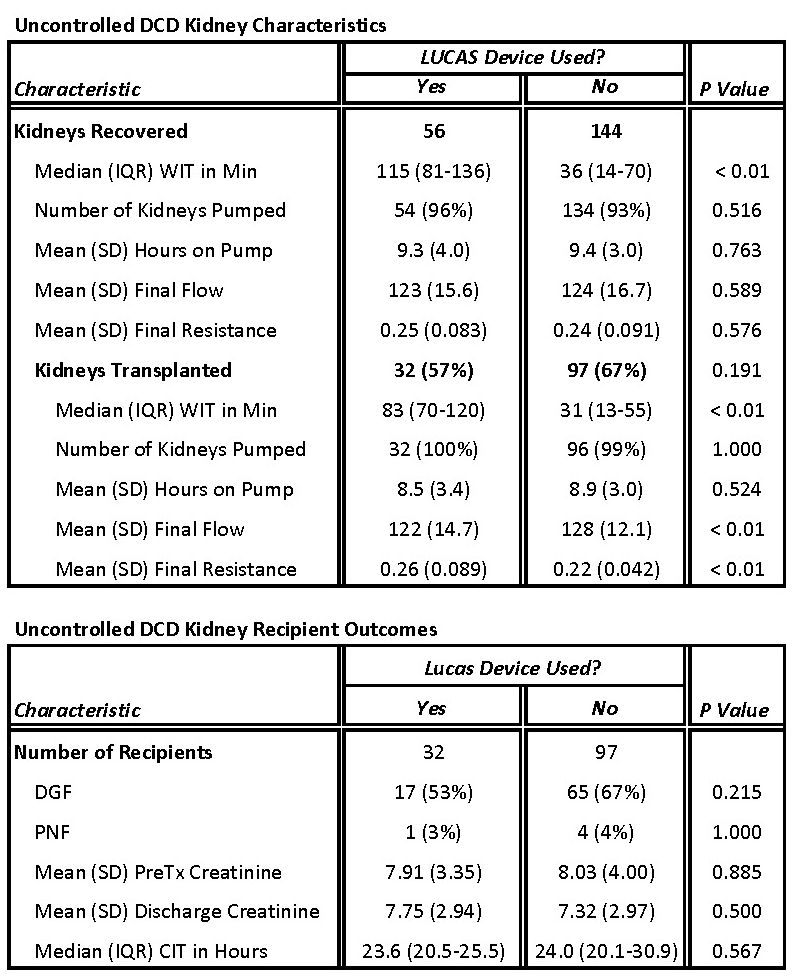

Method: This was a retrospective analysis of 101 uncontrolled DCD donors recovered from 39 hospitals by a single large OPO in the United States between October 2016 and April 2023. An MCC device was used when available at the donor hospital. Data evaluated included Warm Ischemic Time (WIT): the number of minutes from asystole to cross-clamp, pump parameters including final flow and resistance, utilization: kidneys transplanted as a percentage of kidneys recovered, Primary Non-Function (PNF): graft never functioned post-transplant, Delayed Graft Function (DGF): dialysis required within one week post-transplant, and Cold Ischemic Time (CIT): the number of hours between donor kidney cross-clamp to recipient kidney reperfusion.

Results: The mean age was 33 (12.4) years and the primary cause of death was anoxia (51/101, 50.5%) followed by head trauma (45/101, 44.6%) for the 101 uncontrolled DCD donors recovered, with no significant differences observed in age or cause of death between the group of donors given mechanical chest compressions versus those given manual chest compressions. Median WITs were significantly higher for donors given mechanical chest compressions for both kidneys recovered (115 vs 36 min) and kidneys transplanted (83 vs 31 min). While there were no significant differences in final pump parameters for kidneys recovered from the two groups, final flow was significantly lower (122 vs 128) and final resistance was significantly higher (0.26 vs 0.22) for kidneys that were ultimately transplanted from donors that were given mechanical chest compressions. There were no significant differences in kidney recipient outcomes including PNF and DGF between the two groups.

Conclusion: OPOs should develop protocols that include the use of mechanical chest compression devices to increase donation and transplantation from potential organ donors following cardiac arrest. While WIT was significantly greater for kidneys transplanted from donors where mechanical versus manual chest compressions were used, there were no significant differences in recipient outcomes examined including PNF or DGF. The lack of any significant differences in recipient outcomes despite significant differences in WIT indicate that use of mechanical compressions may be more effective in sustaining kidney viability for longer periods of time.